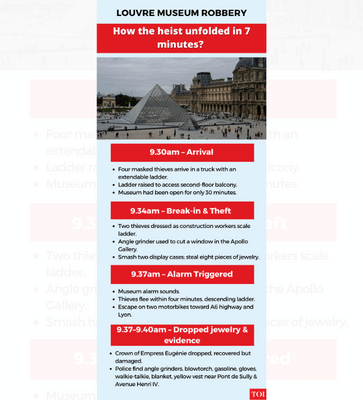

In just under seven minutes, four thieves scaled a furniture lift, broke through a window of the Louvre Museum in Paris , sliced open display cases with angle grinders, and made off with $102 million worth of crown jewels. But the real crime, experts say, is just beginning.

Driving the news: A smash-and-scooter job

Why it matters

The eight stolen items represent some of the finest 19th-century royal jewelry ever created - not just valuable in materials, but steeped in political symbolism and French history:

Each piece is a treasure of “haute joaillerie,” many made by court jewelers Nitot, Lemonnier, and Bapst - names synonymous with the Napoleonic era.

“These are family souvenirs taken from the French,” conservative lawmaker Maxime Michelet said. “Empress Eugénie’s crown, broken and left in the gutter, has become the symbol of the decline of a nation once so admired.”

Context: Why jewels, why now?

The Louvre theft wasn’t an isolated act. Museums across Europe are facing a wave of gem and gold-related robberies:

The big picture

Between the lines: The sell-off has likely begun

The Louvre theft fits a recent pattern of heists where the intent isn’t to resell recognisable artifacts - but to obliterate them into resaleable parts.

“These criminals are just looking to steal whatever they can,” said Christopher Marinello, CEO of Art Recovery International. “They chose this room because it was close to a window. They figured they could break them apart, melt the settings, and vanish.”

Already, experts believe the jewels are being dismantled - melted in garages, diamonds recut by “crooked lapidaries,” and gems sewn into clothes or carried in lining across borders.

“They’re probably in a sack in somebody’s bedroom,” Wittman told The Post, referencing a past case where $50 million worth of stolen art was found behind a refrigerator.

Forget the myth of the eccentric billionaire who commissions a crown heist from his yacht. “That’s unheard of,” said Dutch art sleuth Arthur Brand. “You only see it in Hollywood movies.”

The resale value isn’t what Hollywood suggests. “Thieves rarely get more than 10% of a gem’s market value,” Anthony Roman, a private investigator with art-crime experience, told WSJ. This is because they often have to share profits with insiders who help them avoid detection.

But sometimes 10% of $100 million is more than enough incentive.

What’s next: A race against time

Driving the news: A smash-and-scooter job

- The Sunday morning break-in wasn’t elegant. A ladder truck was parked right outside the Louvre. Angle grinders were left at the scene. A yellow construction vest - part of a costume or an oversight - lay abandoned near the smashed display.

- Most telling: A jewel-encrusted crown, made for Empress Eugénie and set with over 1,300 diamonds and 56 emeralds, was dropped and later found damaged in the street.

- “If the thieves are going to drop a crown, they’re not pros,” said Anthony Roman, a private investigator, to the WSJ.

- Still, they made off with eight significant pieces. What happens now to these objects - part political relics, part historical art, part raw materials - is a story of logistics, desperation, and markets that run parallel to the law.

Why it matters

- The $102 million Louvre jewel heist isn’t just a museum theft - it’s a national and cultural wound. The heist represents a growing threat: an international criminal economy that increasingly targets cultural heritage not for its historical value, but for its commodity worth.

- “If these gems are broken up and sold off, they will vanish from history,” said Tobias Kormind, managing director of European jeweler 77 Diamonds.

- The damage may already be irreversible: “If we don’t find these jewels very quickly, they will disappear for sure,” jewelry historian Vincent Meylan told AFP.

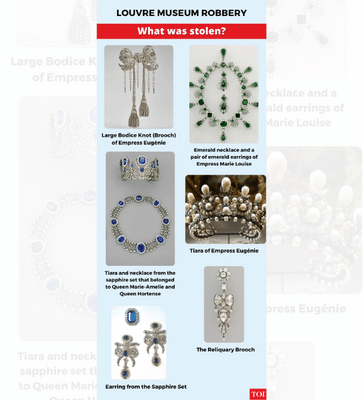

The eight stolen items represent some of the finest 19th-century royal jewelry ever created - not just valuable in materials, but steeped in political symbolism and French history:

- A sapphire diadem, necklace, and single earring linked to Queens Marie-Amélie and Hortense.

- A wedding gift from Napoleon Bonaparte to his second wife, Marie-Louise of Austria: an emerald necklace and matching earrings with over 1,000 diamonds.

- A diamond-studded bodice brooch and tiara worn by Empress Eugénie, the wife of Napoleon III .

Each piece is a treasure of “haute joaillerie,” many made by court jewelers Nitot, Lemonnier, and Bapst - names synonymous with the Napoleonic era.

“These are family souvenirs taken from the French,” conservative lawmaker Maxime Michelet said. “Empress Eugénie’s crown, broken and left in the gutter, has become the symbol of the decline of a nation once so admired.”

Context: Why jewels, why now?

The Louvre theft wasn’t an isolated act. Museums across Europe are facing a wave of gem and gold-related robberies:

- In September, thieves used blow torches to steal $1.75 million in gold nuggets from Paris’s Natural History Museum.

- In Dresden, Germany, a 2019 jewel heist at the Green Vault saw only a partial recovery.

- n 2022, thieves stole ancient gold coins from a Bavarian museum. The loot is still missing.

The big picture

- The black market for precious gems and metals is massive, murky, and largely cash-based. According to the FBI, jewelry theft in the US alone tops $1.2 billion annually, a WSJ report said. Globally, the illicit trade in art and antiquities is estimated between $2 billion and $6 billion, according to Bloomberg.Unlike paintings, jewels don’t require walls to hang on or provenance to establish value. They just need weight and clarity.

- As per the WSJ article, unlike a stolen Picasso, jewels can be transformed - and that's what makes them so tempting. Cut the diamonds smaller, melt down the gold, and any trace of their royal or historical origins disappears.

- From Dubai to Antwerp, Tel Aviv to Delhi, underground networks of unethical dealers, lapidaries, and intermediaries help dismantle and resell these pieces far from their origins.

- “It’s a legal market with gray edges,” art crime expert Erin Thompson told The Post. “You don’t make money as a jewelry dealer by saying no to a good deal.”

Between the lines: The sell-off has likely begun

The Louvre theft fits a recent pattern of heists where the intent isn’t to resell recognisable artifacts - but to obliterate them into resaleable parts.

“These criminals are just looking to steal whatever they can,” said Christopher Marinello, CEO of Art Recovery International. “They chose this room because it was close to a window. They figured they could break them apart, melt the settings, and vanish.”

Already, experts believe the jewels are being dismantled - melted in garages, diamonds recut by “crooked lapidaries,” and gems sewn into clothes or carried in lining across borders.

“They’re probably in a sack in somebody’s bedroom,” Wittman told The Post, referencing a past case where $50 million worth of stolen art was found behind a refrigerator.

Forget the myth of the eccentric billionaire who commissions a crown heist from his yacht. “That’s unheard of,” said Dutch art sleuth Arthur Brand. “You only see it in Hollywood movies.”

The resale value isn’t what Hollywood suggests. “Thieves rarely get more than 10% of a gem’s market value,” Anthony Roman, a private investigator with art-crime experience, told WSJ. This is because they often have to share profits with insiders who help them avoid detection.

But sometimes 10% of $100 million is more than enough incentive.

What’s next: A race against time

- Roughly 100 French investigators, including specialised cultural property units, are combing through surveillance footage, analysing fingerprints, and coordinating with international law enforcement.

- Authorities suspect an organised gang was behind the robbery. The method - a truck-mounted lift, daylight break-in, seven-minute window, quick scooter escape - suggests planning, but not elite precision.

- Still, as Interpol and Europol widen the dragnet, it’s unclear whether authorities can act fast enough to intercept the jewels before they're scattered.

- The Louvre is under intense scrutiny. A Court of Auditors report revealed just 25% of one museum wing had functioning video surveillance. Internal memos show Louvre Director Laurence des Cars warned of “worrying obsolescence” months before the robbery.

- On Tuesday, she was grilled by the French Senate. Meanwhile, Culture Minister Rachida Dati insists security systems “did not fail.”

- But the damage is done. “It’s a wound for all of us,” Dati said. “The Louvre is more than a museum. It’s our national pride.”

- The race to recover the jewels is on. The odds, experts agree, are not good.

You may also like

Liverpool rocked by new injury as Jeremie Frimpong forced off vs Eintracht Frankfurt

CM performs Govardhan Puja

India emerges bright spot for Nestle, Reckitt amid global headwinds

UP: Fire breaks out in residential building in Ghaziabad, officials say few people trapped

India rejects China-backed WTO investment facilitation proposal