Choked airports, weather events, maintenance and staff woes, there’s much that can hold up flight operations. But carriers have a simple strategy to stay on top of flight schedules: inflating the duration of the journey

Depending on which airline you choose to fly, the travel time mentioned in the ticket for a Delhi-Mumbai flight can be less than two hours or stretch to almost three. How’s that possible? Most airlines fly either Boeing or Airbus planes, so they fly at roughly the same speed, more or less at the same altitude, and follow similar routes. So, how do you account for the extra one hour of flying time? That’s where OTP comes in. No, not the one-time password you are so familiar with, but On-Time Performance. Airlines, which, understandably, make a virtue out of punctuality, have long since realised that the safest way to ensure an on-time (or even before-time) performance is by inflating the journey time. That makes late arrival rather difficult.

Basically, airlines do a careful calculation of all factors at play from before a plane takes off till it lands. To be fair, there are many factors an airline doesn’t control. Like bad weather or congestion on the ground and in air before landing in some choked airport like Delhi or Mumbai. Some, though, are very much the responsibility of airlines, like ensuring there are no snags and taking care of other logistical issues like making sure crew are present.

Wide margins

Technically, a flight needs to be pushed back from the boarding gate within 15 minutes of its scheduled departure time to be counted as an on-time departure for the purpose of flight statistics, which are maintained by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA). The scheduled departure and arrival time of a flight is calculated keeping the historical and seasonal flying time (from getting airborne to touchdown) between the origin and destination city pairs and the taxi time at either airport. This is known as the “chocks off” to “chocks on” time, referring to the wedges placed in front and behind aircraft wheels before it is pushed back and after it lands to prevent accidental rolling when parked.

“The usual Delhi-Mumbai flying time is one hour and 40 minutes. Add to that 10 minutes of taxi each at IGIA (Delhi) and CSMIA (Mumbai), giving a total time of two hours. Then, to factor in airport congestion and hovering at destination, the taxi time was increased to, from 20 to, say, 27 minutes. Some airlines added further buffer to their block time — the time an aircraft can start taxiing to the time it comes to a halt at its destination — to ensure they can announce an on-time arrival,” said one pilot. If these inflated flying times are about airlines being smart, it is also a practice that has been driven by growing competition and hectic schedules.

Therefore, unless you are flying on a particularly bad weather day, or a particularly unreliable airline with poor aircraft maintenance/unpaid employees/jet fuel suppliers, or to and from particularly choked airport/s, you are unlikely to miss the boast of “another on-time arrival” on touchdown at the destination by the crew. Queries to big and upcoming airlines — Air India, IndiGo and Akasa — on this issue went unanswered.

It was in 2003 that Indian skies started getting low-cost carriers (LCCs) that democratised air travel. And, with that, air traffic, terminal and runway congestion, too, became a fact of life.

“About two decades back, the total travel time from Delhi to Mumbai was given as 1 hour and 55 minutes. Then, congestion checked in and planes would routinely get delayed on ground and in air. Some smart private airlines started adding a buffer to the journey time to report on-time arrivals. Soon, almost everyone started to do the same, at least on city pairs with choked airports,” said a pilot with over four decades of flying experience. Which brings us to today, when the exact same aircraft type often has different travel times on the same sector. But there’s more here than would appear obvious.

Bragging rights

Arriving ahead of or on schedule triggers a virtuous cascading effect for the airline: the plane can then operate its next flight on time as well with the same buffer for the flight after and so on. That is unless it’s caught in a big weather event like heavy rain or fog or develops a snag en-route or on landing and has to be grounded for checks and maintenance. But there are other reasons why there can be no fixed or standard travel time between two destinations common to all airlines.

How long it takes to fly between any two destinations depends on a number of things, like the routings given (direct or not), weather, wind flow and airport congestion. “If an aircraft gets tailwinds, it will reach its destination faster while headwinds will slow it down. Winters see strong west-to-east jetstreams, which means an Ahmedabad-Kolkata flight could take 10-15 minutes less than the Kolkata-Ahmedabad journey and a LondonDelhi nonstop can take up to two hours less than the Delhi-London,” said a senior commander.

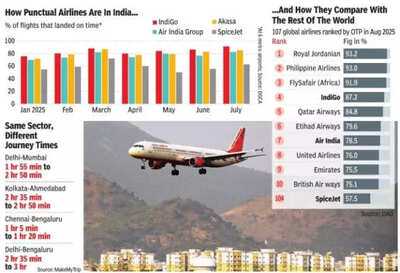

DGCA issues monthly reports for domestic air travel that include, among other data points, OTP data of scheduled domestic airlines based on inputs from six metro airports — Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai, and Kolkata. This “data” is crucial for airlines to project themselves as punctual in the eyes of the domestic traveller.

But tinkering with travel times is not done just for reasons of OTP. Sometimes, Indian carriers that operate long hauls, say between Delhi and London, report an under 10-hour flying time to ensure they can make do with two pilots. Reporting journey time of over 10 hours means they will have to fly with three pilots, which adds to their cost and also requires them to inform DGCA. The regulator routinely flags this issue with Indian carriers whenever it detects anomalies over under-reporting of travel time with a view to carrying fewer than required pilots.

When it comes to reporting inflated travel times on domestic routes, it may suit the airline well, though it also creates several problems on ground.

Blame game

Airlines and operators of busy airports blame each other for air traffic congestion, which is among the potential delays factored in while inflating journey times. While airlines say delays in getting clearance for take-off from or landing at choked hubs is beyond their control, airport operators say that flights failing to operate on time upsets their slot allocation and accentuates OTP issues.

“Airport slots are given per schedules filed by airlines. If airlines don’t adhere to that and planes come ahead of, or after, the time they were supposed to land, then it overlaps with the slot given to some other airline. While some mismatch is understandable depending on weather conditions and routings on a given day, what we see is significant distortion in schedules,” said a senior official at one of India’s busiest airports.

But going ahead, things could improve as India is now seeing a boom in airport infra with Delhi-NCR and Mumbai MMR going to get their secondary airports and Hyderabad and Bengaluru adding to their facilities. Many constrained places like Patna and Chennai, too, will get second airports.

On the airline front, India is now seeing well-funded players like IndiGo and Tata’s Air India Group along with emerging players like Akasa, Star Air and others. These airlines focus on maintaining their young fleets, which, along with added airport infra, should cut down delays to an extent that airlines don’t need to inflate travel times in a desperate bid to win brownie points with flyers.

Depending on which airline you choose to fly, the travel time mentioned in the ticket for a Delhi-Mumbai flight can be less than two hours or stretch to almost three. How’s that possible? Most airlines fly either Boeing or Airbus planes, so they fly at roughly the same speed, more or less at the same altitude, and follow similar routes. So, how do you account for the extra one hour of flying time? That’s where OTP comes in. No, not the one-time password you are so familiar with, but On-Time Performance. Airlines, which, understandably, make a virtue out of punctuality, have long since realised that the safest way to ensure an on-time (or even before-time) performance is by inflating the journey time. That makes late arrival rather difficult.

Basically, airlines do a careful calculation of all factors at play from before a plane takes off till it lands. To be fair, there are many factors an airline doesn’t control. Like bad weather or congestion on the ground and in air before landing in some choked airport like Delhi or Mumbai. Some, though, are very much the responsibility of airlines, like ensuring there are no snags and taking care of other logistical issues like making sure crew are present.

Wide margins

Technically, a flight needs to be pushed back from the boarding gate within 15 minutes of its scheduled departure time to be counted as an on-time departure for the purpose of flight statistics, which are maintained by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA). The scheduled departure and arrival time of a flight is calculated keeping the historical and seasonal flying time (from getting airborne to touchdown) between the origin and destination city pairs and the taxi time at either airport. This is known as the “chocks off” to “chocks on” time, referring to the wedges placed in front and behind aircraft wheels before it is pushed back and after it lands to prevent accidental rolling when parked.

“The usual Delhi-Mumbai flying time is one hour and 40 minutes. Add to that 10 minutes of taxi each at IGIA (Delhi) and CSMIA (Mumbai), giving a total time of two hours. Then, to factor in airport congestion and hovering at destination, the taxi time was increased to, from 20 to, say, 27 minutes. Some airlines added further buffer to their block time — the time an aircraft can start taxiing to the time it comes to a halt at its destination — to ensure they can announce an on-time arrival,” said one pilot. If these inflated flying times are about airlines being smart, it is also a practice that has been driven by growing competition and hectic schedules.

Therefore, unless you are flying on a particularly bad weather day, or a particularly unreliable airline with poor aircraft maintenance/unpaid employees/jet fuel suppliers, or to and from particularly choked airport/s, you are unlikely to miss the boast of “another on-time arrival” on touchdown at the destination by the crew. Queries to big and upcoming airlines — Air India, IndiGo and Akasa — on this issue went unanswered.

It was in 2003 that Indian skies started getting low-cost carriers (LCCs) that democratised air travel. And, with that, air traffic, terminal and runway congestion, too, became a fact of life.

“About two decades back, the total travel time from Delhi to Mumbai was given as 1 hour and 55 minutes. Then, congestion checked in and planes would routinely get delayed on ground and in air. Some smart private airlines started adding a buffer to the journey time to report on-time arrivals. Soon, almost everyone started to do the same, at least on city pairs with choked airports,” said a pilot with over four decades of flying experience. Which brings us to today, when the exact same aircraft type often has different travel times on the same sector. But there’s more here than would appear obvious.

Bragging rights

Arriving ahead of or on schedule triggers a virtuous cascading effect for the airline: the plane can then operate its next flight on time as well with the same buffer for the flight after and so on. That is unless it’s caught in a big weather event like heavy rain or fog or develops a snag en-route or on landing and has to be grounded for checks and maintenance. But there are other reasons why there can be no fixed or standard travel time between two destinations common to all airlines.

How long it takes to fly between any two destinations depends on a number of things, like the routings given (direct or not), weather, wind flow and airport congestion. “If an aircraft gets tailwinds, it will reach its destination faster while headwinds will slow it down. Winters see strong west-to-east jetstreams, which means an Ahmedabad-Kolkata flight could take 10-15 minutes less than the Kolkata-Ahmedabad journey and a LondonDelhi nonstop can take up to two hours less than the Delhi-London,” said a senior commander.

DGCA issues monthly reports for domestic air travel that include, among other data points, OTP data of scheduled domestic airlines based on inputs from six metro airports — Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai, and Kolkata. This “data” is crucial for airlines to project themselves as punctual in the eyes of the domestic traveller.

But tinkering with travel times is not done just for reasons of OTP. Sometimes, Indian carriers that operate long hauls, say between Delhi and London, report an under 10-hour flying time to ensure they can make do with two pilots. Reporting journey time of over 10 hours means they will have to fly with three pilots, which adds to their cost and also requires them to inform DGCA. The regulator routinely flags this issue with Indian carriers whenever it detects anomalies over under-reporting of travel time with a view to carrying fewer than required pilots.

When it comes to reporting inflated travel times on domestic routes, it may suit the airline well, though it also creates several problems on ground.

Blame game

Airlines and operators of busy airports blame each other for air traffic congestion, which is among the potential delays factored in while inflating journey times. While airlines say delays in getting clearance for take-off from or landing at choked hubs is beyond their control, airport operators say that flights failing to operate on time upsets their slot allocation and accentuates OTP issues.

“Airport slots are given per schedules filed by airlines. If airlines don’t adhere to that and planes come ahead of, or after, the time they were supposed to land, then it overlaps with the slot given to some other airline. While some mismatch is understandable depending on weather conditions and routings on a given day, what we see is significant distortion in schedules,” said a senior official at one of India’s busiest airports.

But going ahead, things could improve as India is now seeing a boom in airport infra with Delhi-NCR and Mumbai MMR going to get their secondary airports and Hyderabad and Bengaluru adding to their facilities. Many constrained places like Patna and Chennai, too, will get second airports.

On the airline front, India is now seeing well-funded players like IndiGo and Tata’s Air India Group along with emerging players like Akasa, Star Air and others. These airlines focus on maintaining their young fleets, which, along with added airport infra, should cut down delays to an extent that airlines don’t need to inflate travel times in a desperate bid to win brownie points with flyers.

You may also like

Bihar SIR, PM Modi's 'huglomacy', Gaza: CWC resolutions adopted at Patna meet - details

'BJP has mentally retired Nitish': Kharge says NDA's internal conflict out in open; targets PM Modi

Assam Rifles convoy ambush: Prime accused arrested, Manipur DGP says; arms used in attack recovered

Baby food law's violations abound in face of government inaction

Govt clears DSIR scheme with Rs 2,277 crore outlay to boost innovation, R&D